Towards an Aesthetic Preference in Generative Imagery

Generative AI is becoming as familiar as minimalism has in our interior design, photography on our nights out, and readymades in and out of our fruit bowls.

Remember the urban legend about Jackson Pollock’s red dot? Critics hailed the accidental splash in his black-and-white drip paintings as genius, proof of the artist’s brilliant subconscious at work. Never mind that it might have been unintended, the art world was deluded enough to find meaning in its presence.

This is how art operates: with a determination to create meaning where there is none.

Groundhog Era

Every new medium triggers panic. Impressionism, readymades, minimalism, photography… all arrived to cries of “Meaningless!” But each time, those controversies taught us that it’s the viewer who does the heavy lifting. Agnes Martin knew, ‘The beauty was always in your mind, not in the rose.’

The lesson was about the work required to experience art.

In a report by Everypixel, AI image generators generated more images in their first year of use than humans took in all of shutter history. Magazines are dedicated to it, social media is inundated with it, and elections are being thrown out for fear of its interference.

This ‘new media’ is becoming as familiar as minimalism has in our interior design, photography on our nights out, and readymades in and out of our fruit bowls.

In a sick twist of fate, those saying ‘I could do that’ at the foot of a Joan Mitchell or Agnes Martin, now, supposedly, can do ‘that’ with a prompt. We already spend a great deal of time mentally organising digital content. So, do you want an aesthetic preference in slop? Would you like to look for meaning when there is none?

But Is It Art?

The work of art happens at three levels: the labour of making, the cognition of viewing, and the collaboration between artist and viewer in an encounter. Maybe AI-generated images are new media in the truest sense, continuing to push the burden of meaning further onto the back of the viewer. An age-old challenge to the title ‘Artist’ and ‘Art’.

The art world is scrambling to establish criteria for AI art’s legitimacy, but these definitions miss the point by trying to locate quality in the output rather than the process. This assumes some images contain more meaning than others. But time tells, art contains precisely as much meaning as any individual viewer sees in it.

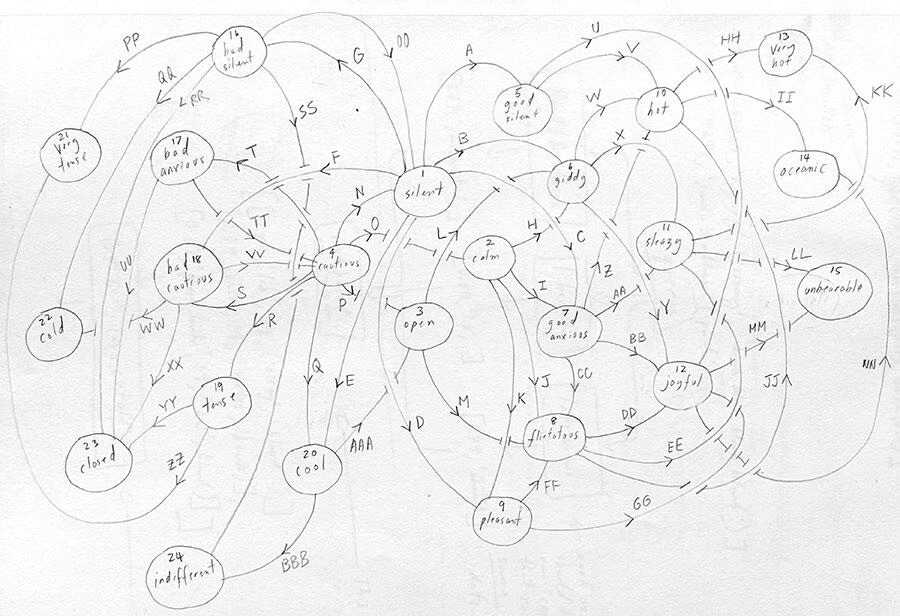

Paul Chan inadvertently proved this point in an article for Frieze. He trained a model on his own work to answer interviews and email questions as himself. The model suggested his voice could be distilled into his output, his productivity, the patterns in what he’d already produced. He was what he had made. His work became his identity. This is the trap of treating art as a result rather than a process. Chan diagnosed the absence in generated images, the part in between what’s made and why it’s made.

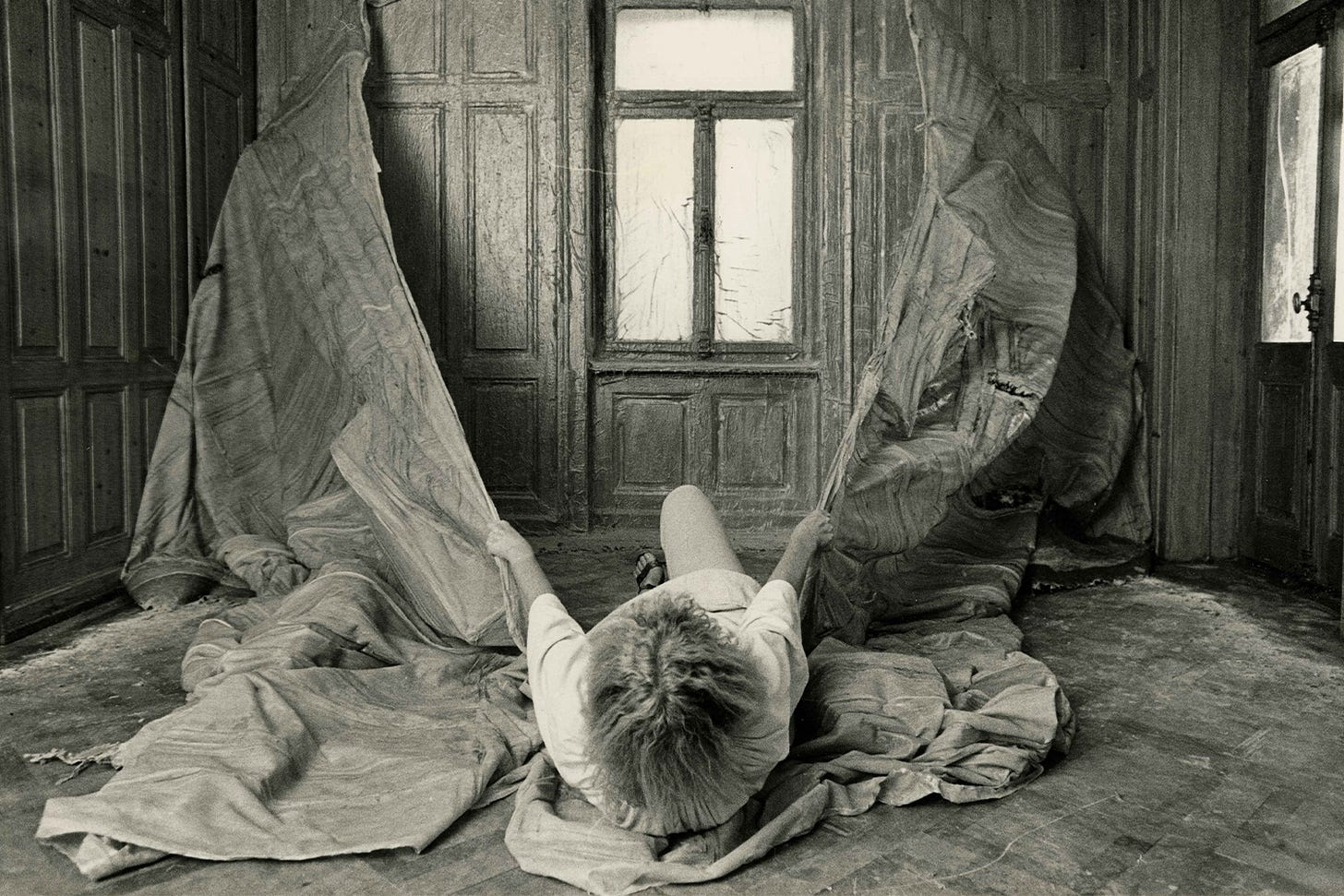

Consider Heidi Bucher, who exorcised physical places from her memory by skinning trauma from the oppressive architecture of patriarchal institutions, the domestic spaces that confined her. Her production is tied tightly to her experience, but it was the process, the physical act of pressing latex to walls, waiting for it to cure, and peeling away layers of skin, that severed her from those memories. Bucher wasn’t what she made. That labor, of creation, was how her relationship to memories changed, and what Chan’s AI can’t replicate. The artwork was her experience.

We’ve traditionally assessed art through a tidy trinity of concept, execution, and impact, but generative AI images mess with all three. The concept might be human but the execution is algorithmic; so, the impact depends on framing. Curators must consider whether to exhibit the prompt, the process, the output, or the entire system.

Artwork

The discussion isn’t about whether AI can make art, but what the result requires of us (the reader, the viewer, the documenter), and of its maker.

The red dot in Pollock’s painting might have been an accident, and it shows art’s provocation to find meaning where it isn’t signposted. But if meaning can be generated infinitely, is looking harder meaningless? The choice isn’t whether or not to argue the presence of meaning in generative images, but whether the labour of looking and interpreting is still a contemporary collaboration that contributes to a work of art.

A curator’s role is many, but one is to guide a viewer’s interpretive labour. Perhaps our work now is to prioritise and utilise (physical) spaces where the labyrinthine, difficult labour of construction and interpretation can occur, where red dots can be made by accident and considered significant by those who linger.

Further readings: Allado-McDowell, K. “Am I Slop? Am I Agentic? Am I Earth? Identity in the Age of Neural Media.” Neural Media, February 19, 2025, (here) | Chan, P., “The Psychology of Your AI Self-Portrait.” Frieze Magazine, no. 253 (September 2025) | Christie’s, 2025, “What Is AI Art?” Christie’s, 7 February, (here) | Davis, B., Stephanie Dinkins, Mike Pepi, Noam Segal and Christopher Kulendran Thomas. “Can Machine Creativity Truly Exist?.” Frieze Magazine, no. 239 (Nov./Dec. 2023) | Valyaeva, A., 2023, ‘People Are Creating an Average of 34 Million Images Per Day. Statistics for 2024,’ Everypixel Journal, 15 August, (here)