What Happens to Memory when Home is Destroyed?

Do Ho Suh, Heidi Bucher, and Mona Chalabi approach the weight of home in radically different ways.

AI SUMMARY:

The piece argues that homes are never just physical structures but carry weight as memories, attachments, and imprints on the body. Through the works of Do Ho Suh, Heidi Bucher, and Mona Chalabi, it shows different artistic approaches to the tension between architecture and memory. Suh recreates homes as ghostly presences that linger even after departure; Bucher violently peels and releases spaces, confronting patriarchy embedded in domestic walls; Chalabi documents homes erased by domicide, exposing the injustice of forced loss. Together, they illustrate that homes shape us whether preserved, shed, or destroyed, and that in today’s world—where war, conflict, and disaster continue to raze houses—leaving is always heavy, but obliteration is heavier still.

Why do we add an AI summary to our posts? We value your time and want to provide you with more information before you read the entire text.

Article written by Emily Daymond-King for Looking Forward

Homes are never only physical. They are imprints on the body, memories carried when walls are left behind or destroyed. From sleeping, eating, and loving in one place to leaving it for another, transition requires adjustment, and homes tone us like dumbbells. Contemporary artists have long wrestled with how architecture and memory intertwine — whether as attachment, resistance, or grief. After visiting The Genesis Exhibition: Do Ho Suh: Walk the House at Tate Modern, I felt that leaving a place is not absence, but another form of attachment. Like Suh, ‘home’ weighed more once I’d packed up and left it.

This tension animates Suh; for him, the weight of ‘home’ is not abstract but material. Nest/s (2024) is a merging of three homes in one hallway, doors, fire extinguishers, lights and all. He rubs his former homes in paper and granite, and brings them back to a ghostly life in polyester and steel, recreating their physical presence for us to walk through his recollection.

Rubbing/Loving: Seoul Home (2013-2022), a paper rubbing of a Hanok (built by Suh’s father), exudes humility, and details are revealed with close attention. Reassembled to scale on an aluminium frame, the papers hover just above the floor, freckled with weather after months of exposure to the wind, rain and sun following the initial rubbing. The place was subject to its environment’s graces, and Mother Earth* is a discerning landlord.

Heidi Bucher ‘skins’ architecture by peeling latex sheets from walls and floors. Where Suh lingers, she releases. As physical and painful as it sounds, her Hauträume (roomskins), analysed here by Carolina Lio, are blisters. Since the 1980s, Bucher has been creating physically demanding Hauträume that liberate memories from space, the artist from their hold. For Bucher, patriarchy haunts her interiors: domestic architectures that speak of gendered discipline, against which her practice wages its slow liberation. Her works inevitably atrophy over time, Mother Earth disrupts their forms, and the natural ebb of gravity sags her skin. Unlike Suh, these spaces are to be freed of, to be exorcized from. Both artists work through skin: Suh’s rubbings press against walls to capture their presence, while Bucher’s latex peels tear them away. If Suh creates ghosts to be carried, Bucher performs a ritual release, confronting patriarchal structures embedded in the domestic sphere.

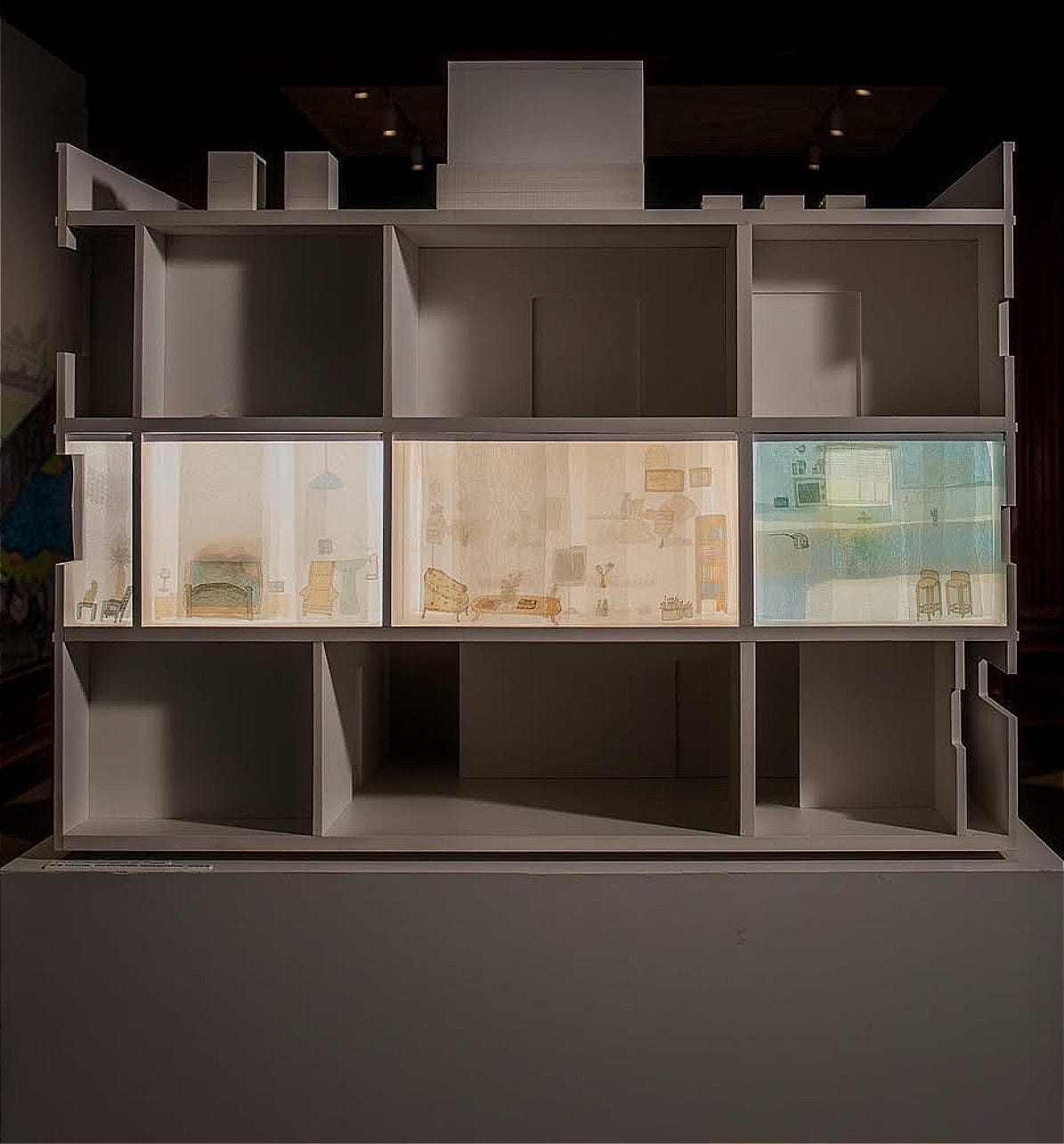

What happens when these memories are destroyed with the home itself? What happens when it is a human choice to destroy a home already claimed? These questions shadow Mona Chalabi’s Patterns of Life, which was shown earlier this year at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Triennial – Making Home, in New York. Patterns of Life comprises three white, dollhouse-sized architectural models. Each four-storey building has a cross-section exposing the interiors, of which only one floor, one apartment, is decorated. Translucent sheets of fabric, each featuring drawings of different household items, overlay one another to create a scene. TVs, chairs, microwaves. Light shines through the windows and door cutouts.

The gallery wall is covered in Chalabi’s coloured-pencil drawings, maps of the towns and cities where these three buildings once stood, which have been destroyed: sites of domicide through social upheaval, urban development, and military conflict. Each home belonged to a family that Chalabi had followed and interviewed for the project, whose homes were reduced to memory. On the back wall, Chalabi has written, ‘70% of homes in Gaza have been damaged or destroyed, including X’s.’

In Chalabi’s work, our three artists triangulate. Suh and Bucher exhibit ghosts of their ‘places’: one a growing memorial, the other an epitaph. Chalabi’s is a vociferation against injustice, the pain of forcible severing. Together, they remind us that a house is never neutral: it is a vessel of memory, discipline, or despair. And while these artists grapple with the persistence of memory, the present forces us to confront its fragility. As wars level cities and climate disasters uproot millions, homes are not just left; lives are obliterated. To leave is heavy, but to lose everything is heavier still. Memory may be all we have.

“Do Ho Su: Walk the House” is on view at Tate Modern until 26 October 2026

Further Readings: Kerbel, Janice. “Home Sweet Home: Janice Kerbel Talks to Do Ho Suh.” Tate Etc., 20 March 2025. (here) | Lio, Carolina. “Heidi Bucher: Rooms as Skins.” Looking Forward – Art Notes, 4 September 2025. (here) | “O’Hagan, Sean. “‘Memories of These Places Never Leave You’: Artist Do Ho Suh and the Fabric of Home.” The Guardian, 13 April 13 2025. (here) | Steer, Emily. “Meet 5 Artists Using Architecture as Memory Machines.” Artnet News, 9 December 2024. (here)